The Murder of Margaret Quinn

In 1908, Richard Quinn shot his wife on the streets of Everett, Washington. His botched execution led to a conspiracy against a newspaper editor in nearby Bellingham.

The early lives of Maggie Murphy and Richard Quinn

Margaret “Maggie” Murphy was born in about 1878 in Ireland. When she was a young girl, her family moved to Govan, Scotland. Her father Thomas was a sailor, often leaving his wife Margaret to care for their children alone. Maggie immigrated to the United States sometime around 1901. She married Richard Quinn in Michigan in 1903.

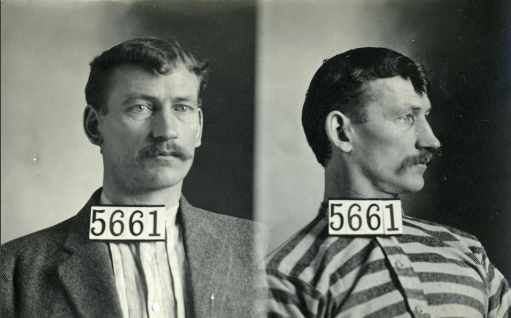

Richard Quinn was born June 3, 1878, in Mason County, Michigan, to John and Caroline (Weldon) Quinn. He grew up on a farm in Summit, Michigan. He married his first wife, Ada Leona Mattison, on May 30, 1898, in Hart, Michigan. Their only child, Jennie, was born the following year, and tragically died of pneumonia in 1901 at the age of one year and eight months. A little over a year later, Richard and Ada divorced. Richard soon after met and married Maggie, which was the catalyst for the untimely end of Maggie’s life.

Problems in the marriage turn deadly

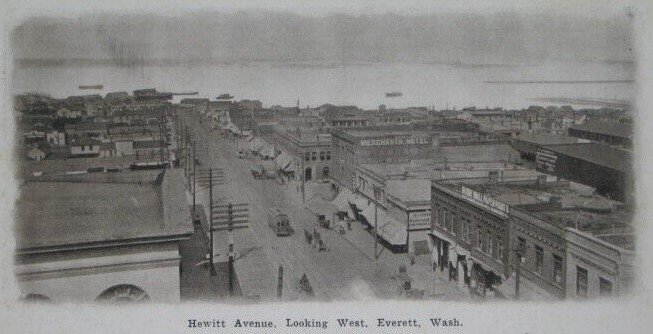

Richard and Maggie moved to North Dakota in 1904, and then to Washington in 1907. After years of arguments and relationship troubles, Richard and Maggie settled in Everett in 1908, in an attempt to find work and stability. The couple initially did well in their new home, with Richard finding work as a fireman at the Ferry-Baker mill. He was a heavy drinker, however, and soon lost his job. He found work elsewhere sawing shingle bolts, but his drinking had already caused problems in his marriage, and, by August, Maggie left him. She found work caring for the children and household of a local widower, and Richard continued his drinking. He was often found drunk and complaining about his wife to anyone who would listen, insisting that he would shoot her.

By September, Margaret had found more pay working at a restaurant. On September 17th, Richard was seen at the Rainier saloon, carrying his rifle and threatening to shoot his wife. No one believed him, as it wasn’t uncommon for him to make this threat. The next day around 4 p.m., Richard called Maggie and told her to meet him at her brother Andrew’s house to retrieve her trunk immediately or he would throw it out. As she made her way to retrieve her property, Richard rode up on his horse. At the corner of 20th and Summit Ave, he dismounted. Maggie stood alongside his horse, patting its neck tenderly, when Richard said, “Good-bye, Maggie,” and shot her in the chest. The muzzle of the rifle was so close to her body that it scorched her dress. The bullet went through her pericardium, diaphragm, liver, and spleen before exiting her body.

A neighbor named William Watts heard both the shot and Maggie’s scream and came running outside to see Maggie stagger through the gate of another neighbor’s yard; she collapsed on the porch. Watts ran back into his house to retrieve his own rifle. He ran back outside and found Richard mounted on his horse and pointing the rifle once again toward Maggie. Watts pointed his rifle at Richard and threatened to shoot if he fired at Maggie again, and that sent Richard galloping off. Word was sent to the police force, who immediately began rounding up a posse to find and detain Richard. An hour after the shooting, however, along with his brother-in-law Bert Mason, Richard showed up at the police station and turned himself in.

Mortally wounded, Maggie was brought to her brother’s house nearby and given opiates to relieve her pain. She initially held on and stayed conscious and it was thought perhaps she could recover. She was brought to Providence Hospital where it was later determined that her wound was indeed fatal, and she eventually succumbed to her wounds a few minutes past 1 a.m. on September 23rd. Richard was informed of his wife’s death the next morning as he sat in jail, though he reportedly showed no emotion upon hearing the news. He asked to view her body before burial but his request was denied. Maggie was buried at Evergreen Cemetery.

The aftermath of murder

Richard’s excuse for the shooting was that it had been an accident: he was drunk and not in control of himself. Regardless, he was indicted for first-degree murder. On December 14, 1908, Richard was found guilty of first-degree murder and sentenced to hang. It was reported that, upon hearing the verdict, Richard calmly reached into his pocket, pulled out a paper and some tobacco, and rolled a cigarette.

After the rounds of appeals to the Supreme Court afforded to all capital punishment sentences, the guilty verdict and execution sentence were upheld. In February 1910, Richard was transported to Walla Walla prison, where his execution was scheduled to take place on April 15th. Mary (Quinn) Mason, however, wasn’t about to give up her brother’s life without a fight. Mary campaigned tirelessly for a stay of execution, collecting signatures from 500 Everett residents, including most of the jurors who had convicted Richard in the first place. Governor Hay issued a reprieve on April 13th until May 12th to review the case but ultimately declined to issue a stay of execution.

On Friday, May 13, 1910, in Walla Walla, Richard would become the 13th prisoner to be executed at the Walla Walla gallows; a spooky coincidence that was perhaps an ominous foreshadowing of the disturbing outcome of the execution. Although Richard had refused spiritual counseling while incarcerated and had acted as though he cared little about his actions and their consequences, he paled when told the night before of the impending execution the following morning. He did not sleep well, spending his last night writing letters. Early on Friday morning he ate breakfast and dressed in his black burial suit. The guards read him his execution proclamation and led him to the gallows. He requested a cigarette, which was denied.

“The condemned man walked to the gallows as cheerfully as he would take a morning walk in the woods. The usual formalities were proceeded with and after Quinn had made the statement declaring his innocence and saying the shooting of his wife was done accidentally, the trap was sprung. A horrible scene followed. The drop apparently had no effect on Quinn. He swayed from side to side moaning, ‘For God’s sake, take me up and drop me again, boys,—boys, this is awful.’ His brain was so clear that he was able to unbuckle the straps which bound his arms. Finally after the terrible scene, lasting many minutes, during which spectators and officials stood horror-stricken and unable to aid in hastening the death, unconsciousness came, the body ceased to sway and then after 22 1/2 minutes of the sickening scene life was pronounced extinct and the body was cut down. Investigation showed the [cords] on the back of Quinn’s neck abnormally developed, preventing the rope from sinking into the flesh to strangle the vitcim expeditiously and he died a lingering death.”

The Wenatchee Daily World, Wenatchee, WA. 13 May 1910. Page 1.

Richard’s body was released to his sister and buried in the Walla Walla prison cemetery.

A newspaper editor is targeted for doing his job

Due to the extraordinarily gruesome outcome of the hanging, newspapers printed a description of Richard’s botched execution despite the Washington law against publishing the details of any execution. W. D. Dodd, editor of The Bellingham Herald, received a lot of criticism from competitors for publishing the details and publicly challenged any offended party to turn him in. On May 19th, a warrant was signed by Judge Featherkile on the request of A. A. Rogers, and Dodd pleaded not guilty in court. He requested a speedy trial, which took place the following morning. During the trial, it was revealed that Rogers likely had a personal vendetta against Dodd and his publication, as newspapers owned by acquaintances of Rogers had also published the details of the execution with no such offense taken from Rogers. Additionally, before making his complaint at the prosecutor’s office, Rogers had spoken to Bert Hammerstrom: the man who had written the article in a rival newspaper slamming Dodd for The Herald’s publication. The defense produced multiple newspapers that had published the same amount of detail as The Herald, but ultimately it was up to the jury to decide whether Dodd was guilty of breaking the law. They deliberated for a mere eight minutes before returning a verdict of not guilty.